The Man Who Fell to Earth by Walter Tevis

The Man Who Fell to Earth by Walter Tevis

I’ve said it before in The Clarion: I am not a fan of sci-fi. Last time I was talking about ‘The Death of Grass’, which left me horrified. It was written with the calibre of John Wyndham, but will all the nightmare of the best apocalyptic fiction.

And it is therefore with equal surprise that I discover that it wasn’t a one-off experience. Despite some reticence I really enjoyed Walter Tevis’ novel ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’, famously brought to life as a film of the same name in the 1970’s by visionary director, Nicolas Roeg.

Both books don’t feel like sci-fi at all, much to the credit of the quality of writing itself. In fact, Tevis’ other famous novel was ‘The Hustler’ (also made into a famous film), which is a gritty tale of pool sharks.

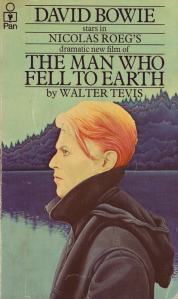

My edition was the original film tie-in, with a painting of the iconic image of David Bowie as the mysterious Thomas Newton/alien. A version of this also appeared on Bowie’s own ‘Low’ LP sleeve and while the paperback states the music soundtrack would be ‘available on RCA’, this never happened, although Bowie is said to have scattered musical doodlings for or influenced by his role in the film across albums in the 70’s. Indeed, another image from the film appear as the cover of ‘Station to Station’.

For sure, it is now hard to think of Newton being anyone but Bowie, and this is to the film’s credit. The casting and feel is spot-on and mirrors the book beautiful – complements it where you, like me, have seen the film, but have yet to read the book. And the book is far better as it simply doesn’t have those wayward forays into sexual exploration and nor do we have to endure occasionally shaky-acting.

But putting aside the movie, Tevis’ work is full of compassion, longing and thought on the notion of being a stranger in a strange land. It has more to do with ‘The Catcher in the Rye’ or ‘The Bell Jar’ than it does traditional sci-fi. The writing is taught, dialogue believable and pace just right. At times it reminded me of ‘The Swimmer’ (also a famous book and film), and at others’ a feature-length and more mature ‘Twilight Zone’ or ‘Tales of the Unexpected’.

‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ is also a deeply humane book. It takes the concept of looking at man through the mirror of an alien point of view. But that alienation is one many of us feel. We feel it when we are teenagers and when we are alone in a crowd in a foreign place or visiting a new city. We feel it with wonder when we see ourselves in a moment of silence looking at art in a gallery or catch ourselves aware of ourselves as a species when at the zoo. But most of all, we feel when the world – full of humans – seems incredibly lonely.

Newton feels the gravity of earth heavy on his disguised frame; but he feels the pointlessness of existence and man’s folly just as heavily: “a heavy lassitude, a world-weariness, a profound fatigue with this busy, busy, destructive world and all its chittering noises.”

The novel ponders quietly the big themes without pushing any particular agenda or world-view. Newton considers, for example “this peculiar set of premises and promises called religion.” But finds solace in some types of music.

Providing counter-balance is Professor Bryce. He’s not quite the narrator and certainly not entirely likeable either. In the movie he’s an aging playboy, but the novel gives his character more tragedy and more drink. Imagine Charles Bukowski as a failed university science professor. He’s not an idiot and indeed, it is through his fascination with Newton’s inventions which drive the narrative to a truly horrible conclusion where, as Tevis puts it, the reveal has the monkeys performing the tests on the humans.

In their parrying Newton and Bryce become friends, comrades and critics. They argue over the philosophical position of science and its funding: “Somebody has to make the poison gas.” And this leads us to the primary concern of the novel: the destruction of mankind by his own kind.

This is a moving and tragic novel of apathy and alienation. It is expertly crafted and still yet a page-turner.

You might think that – written in 1963 – and famously filmed in the 70’s with a very 70’s ‘feel’ ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ is set in the 1970’s, but in fact it is set in the then future of the mid-late 1980’s. It predicts global nuclear war within 30 years of that. Of course, the Cold War was raging in the 60’s and Tevis rightly predicted it would still be so by the 1980’s. But the fall of the Soviet Union was not something explored then. This does not make Tevis’ forecast flawed as the same deadly arsenal continues to exist today and, as we see in recent months, it no longer requires opposing ideology to create the tension between old and emerging super powers: resource and territory dispute continue to be enough.

It is a warning that we can all yet fall to earth.